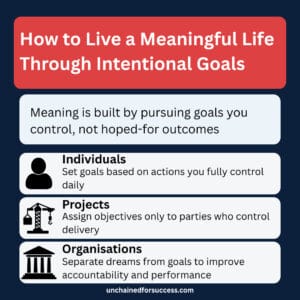

How to Live a Meaningful Life Through Intentional Goals

Introduction: Moving Beyond Meaning

At the start of the year, many people return to the same question: how to live a meaningful life. The question is not driven by lack of effort, but by a sense that energy is being spent without building something that truly matters.

In last week’s blog, we explored why meaning must be the anchor for the year. This article moves the conversation forward. Meaning on its own does not change outcomes. What matters now is how that meaning is translated into action, decisions, and daily behaviour.

A meaningful life is not sustained by reflection alone. It is built through intentional choices, expressed consistently over time.

Why Meaning Often Fails to Show Up in Daily Life

Most people already know what matters to them. Family, growth, contribution, health, faith, financial stability, impact. The issue is rarely a lack of values. The issue is translation.

Meaning sits at a high level, while daily life operates through calendars, commitments, and competing demands. When the two are not connected, urgency takes over. People react to what is loudest rather than what is most important.

Research in positive psychology consistently shows that purpose improves wellbeing and resilience only when it is expressed through behaviour, not when it remains at the level of intention alone. Without a practical bridge, meaning fades under pressure.

Dreams and Goals Are Not the Same Thing

This is where many individuals, leaders, and organisations go wrong.

A dream is a desired outcome. It describes what you would like to happen. Dreams often depend on other people’s decisions, external processes, or circumstances outside your direct control.

A goal, by contrast, is an objective you can act on directly. It sits within your control. You can execute it regardless of how others respond.

Dreams are valuable because they give direction.

Problems arise when dreams are mistaken for goals and people are held accountable for outcomes they do not control.

Why SMART Objectives Can Still Be Dreams

This confusion is often reinforced by how goals are commonly taught.

An objective can be:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Relevant

- Time-bound

In other words, perfectly SMART and still not be a goal for the person it is assigned to.

SMART describes clarity, not control.

If the achievement of an objective depends on decisions or actions that sit outside someone’s authority, then for that person it remains a SMART dream, not an executable goal.

Organisational research has repeatedly shown that performance improves when individuals and teams are accountable only for outcomes within their control, rather than results dependent on external decisions or approvals.

Control Must Sit with the Right Party: A Practical Example

Consider a common project scenario.

A supplier is contracted to design and construct an asset. The client must then complete internal documentation and progress regulatory or statutory approvals before the asset can be accepted or commissioned.

If a client sets the following objective for the supplier:

“Achieve regulatory approval for the asset by September.”

That objective may be clear and time-bound, but it is not a goal for the supplier.

Regulatory approval depends on:

- client-controlled submissions and governance,

- internal approval processes,

- external regulators’ timelines and decisions.

For the supplier, this is a SMART dream.

The correct approach is to align objectives with control:

- Supplier goal: deliver a compliant constructed asset and full documentation pack by an agreed date.

- Client goal: complete internal processes and obtain regulatory approval by a defined milestone.

When responsibility and control are aligned, accountability becomes fair, performance improves, and frustration reduces.

The Same Mistake Appears in Personal Life

The same pattern plays out for individuals.

An individual might set an objective such as:

“Get married by the end of the year.”

It may be specific and time-bound, but it depends on another person’s decision and timing. For that individual, it is a dream, not a goal.

The dream is valid. What must change is the execution. Goals should focus on actions, behaviours, and preparation that sit within the individual’s control. This removes misplaced pressure and replaces it with agency.

How to Live a Meaningful Life Requires Goals You Control

If you want to understand how to live a meaningful life in practice, this is the turning point.

Meaning becomes real when it is translated into goals that:

- sit within your control,

- can be executed regardless of external responses,

- and reflect what genuinely matters to you.

Intentional goals anchor responsibility correctly. They prevent people from blaming themselves for outcomes they do not control and allow effort to compound rather than scatter.

This is where purpose stops being abstract and starts shaping daily life.

The Three Levels of Goals That Turn Meaning Into Action

Once the difference between dreams and goals is clear, structure matters.

Outcome Goals: Direction

Outcome goals describe the direction you are building towards. They are often close to dreams, but they provide orientation rather than daily instruction.

Performance Goals: Evidence of Progress

Performance goals translate direction into measurable progress. They help you assess whether movement is happening without pretending you control everything.

Process Goals: What You Fully Control

Process goals define the actions you execute consistently. These sit entirely within your control and are where meaningful change actually occurs.

When these three levels are aligned, effort becomes focused and sustainable.

Why Control Matters More Than Motivation

Progress rarely fails because of lack of motivation. It fails because responsibility is placed in the wrong place.

When goals depend on outcomes outside your control, effort becomes fragile. When goals focus on controllable actions, consistency becomes possible even under pressure.

A meaningful life is not built by waiting to feel motivated. It is built by executing what you control long enough for results to follow.

Applying This in Real Life

For individuals, living meaningfully means designing goals that reflect values and sit within personal control.

For leaders, businesses, and projects, it means assigning objectives to the party that can actually deliver them. This single shift improves trust, performance, and outcomes more than any motivational intervention.

Meaning emerges when responsibility and control are aligned.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Setting dreams and calling them goals

- Assigning objectives to people who do not control them

- Confusing activity with progress

- Using SMART as a substitute for thinking about control

Avoiding these mistakes protects momentum as the year becomes more demanding.

Conclusion: Meaning Is Built, Not Discovered

If you want to know how to live a meaningful life, stop waiting for meaning to appear and start building it deliberately. Meaning grows when goals reflect what matters and responsibility sits where control exists.

When intention is translated into controllable action, fulfilment becomes a by-product of alignment, not a feeling you chase.

Next week, we will explore why even well-designed goals fail without a strong personal “why” and how to anchor goals so they hold under pressure.

References

- Unchained: Success Unlocked – A Proven Framework for Achieving Goals by Clement Kwegyir-Afful

- Purpose in Life as a System That Creates and Sustains Health and Well-Being: An Integrative, Testable Theory by Patrick E. McKnight and Todd B. Kashdan

- Application of the Controllability Principle and Managerial Performance: The Role of Role Perceptions by Michael Burkert, Franz Michael Fischer, and Utz Schäffer

- Purpose in Life as a Predictor of Mortality Across Adulthood by Patrick L. Hill and Nicholas A. Turiano

- Effect of Locus of Control on Job Performance: Evidence from Australian Panel Data byLe Bao Ngoc Nguyen, Dusanee Kesavayuth, and Poomthan Rangkakulnuwat